Myth #1: Electric Vehicles are worse for the climate than ICE cars because of the power plant emissions.

Myth #2: EV s are worse for the climate than ICE because of battery manufacturing.

Myth #3: The increase in EVs entering the market will collapse the power grid.

Myth #4: EVs don’t have enough range to handle daily travel demands.

Myth #5: Electric vehicles are not as safe as comparable gasoline vehicles.

Myth #1: Electric vehicles are worse for the climate than gasoline cars because of the power plant emissions.

- FACT: Electric vehicles typically have a smaller carbon footprint than gasoline cars, even when accounting for the electricity used for charging.

Electric vehicles (EVs) have no tailpipe emissions. Generating the electricity used to charge EVs, however, may create carbon pollution. The amount varies widely based on how local power is generated, e.g., using coal or natural gas, which emits carbon pollution, versus renewable resources like wind or solar, which do not. Even accounting for these electricity emissions, research shows that an EV is typically responsible for lower levels of greenhouse gases (GHGs) than an average new gasoline car. To the extent that more renewable energy sources like wind and solar are used to generate electricity, the total GHGs associated with EVs could be even lower. (In 2020, renewables became the second-most prevalent U.S. electricity source.1 ) Learn more about electricity production in your area by visiting EPA’s Power Profiler interactive web page. By simply inputting your zip code, you can find the energy mix in your region.EPA and Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Beyond Tailpipe Emissions Calculator can help you estimate the greenhouse gas emissions associated with charging and driving an EV or a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) where you live. You can select an EV or PHEV model and type in your zip code to see the CO2 emissions and how they stack up against those associated with a gasoline car.

Myth #2: Electric vehicles are worse for the climate than gasoline cars because of battery manufacturing.

- FACT: The greenhouse gas emissions associated with an electric vehicle over its lifetime are typically lower than those from an average gasoline-powered vehicle, even when accounting for manufacturing.

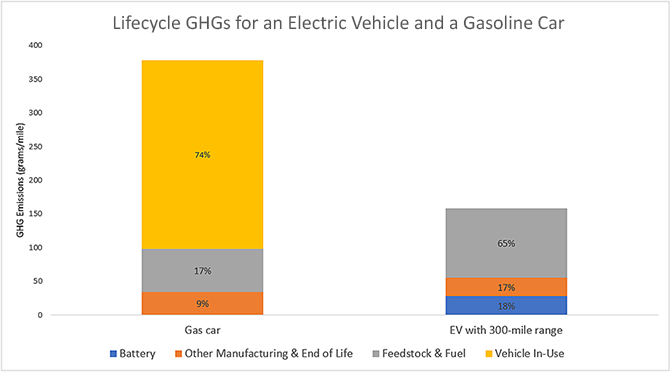

Some studies have shown that making a typical EV can create more carbon pollution than making a gasoline car. This is because of the additional energy required to manufacture an EV’s battery. Still, over the lifetime of the vehicle, total GHG emissions associated with manufacturing, charging, and driving an EV are typically lower than the total GHGs associated with a gasoline car. That’s because EVs have zero tailpipe emissions and are typically responsible for significantly fewer GHGs during operation (see Myth 1 above).For example, researchers at Argonne National Laboratory estimated emissions for both a gasoline car and an EV with a 300-mile electric range. In their estimates, while GHG emissions from EV manufacturing and end-of-life are higher (shown in orange below), total GHGs for the EV are still lower than those for the gasoline car.

Estimates shown from GREET 2 2021 are intended to be illustrative only. Estimates represent the model year 2020. Emissions will vary based on assumptions about the specific vehicles being compared, EV battery size and chemistry, vehicle lifetimes, and the electricity grid used to recharge the EV, among other factors.

The blue bar represents emissions associated with the battery. The orange bars encompass the rest of the vehicle manufacturing (e.g., extracting materials, manufacturing and assembling other parts, and vehicle assembly) and end-of-life (recycling or disposal). The gray bars represent upstream emissions associated with producing gasoline or electricity (U.S. mix), and the yellow bar shows tailpipe emissions during vehicle operations.

Recycling EV batteries can reduce the emissions associated with making an EV by reducing the need for new materials. While some challenges exist today, research is ongoing to improve the process and rate of EV battery recycling.

For more information on EV battery development and recycling, visit: U.S. Department of Energy’s ReCell Center and National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries, 2021-2030 (pdf) (June 2021, report published by the Federal Consortium for Advanced Batteries)

Myth #3: The increase in electric vehicles entering the market will collapse the power grid.

- FACT: Electric vehicles have charging strategies that can prevent overloading the grid, and, in some cases, support grid reliability.

It is true that the increasing number of electric vehicles (EVs) on the road will lead to increased electricity demand. Yet, how that impacts the grid will depend on several factors, such as the power level and time of day when vehicles are charged, and the potential for vehicle-to-grid (V2G) charging 3 among others.- EVs can be charged at off-peak times, such as overnight, when rates are often cheaper. Even with a mix of charging times (so not all nighttime charging), research indicates that sufficient capacity will exist to cover EVs entering the market in the coming years.4 And further down the road, when renewables make up a larger part of our energy mix in many regions, switching to more daytime charging (when some renewables like solar generate energy) with some energy storage capability should allow the grid to handle increases in EV charging.5 California leads the country with more than 1 million electric vehicles and EV charging currently makes up less than 1% of the state’s grid total load, even during peak hours.6

- Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) charging allows EVs to act as a power source that may help with grid reliability by pushing energy back to the grid from an EV battery. This is done by allowing EVs to charge when electricity demand is low and drawing on them when that demand is high.

Myth #4: Electric vehicles don’t have enough range to handle daily travel demands.

- FACT: Electric vehicle range is more than enough for typical daily use in the U.S.

EVs have sufficient range to cover a typical household’s daily travel, which is approximately 50 miles on average per day.7 The majority of households (roughly 85%) travel under 100 miles on a typical day. Most EV models go above 200 miles on a fully-charged battery, with nearly all new models traveling more than 100 miles on a single charge. And automakers have announced plans to release even more long-range models in the coming years. Range estimates for specific EVs are available from the Find A Car tool on www.fueleconomy.gov—click on the car you are interested in, and check out the “EPA Fuel Economy” line in the table. How you drive your vehicle and the driving conditions, including hot and cold weather, also affect the range of an EV; for instance, researchers found on the average range could decrease by about 40% due to cold temperatures and the use of heat.8

Myth #5: Electric vehicles are not as safe as comparable ICE vehicles.

- FACT: Electric vehicles must meet the same safety standards as conventional vehicles.

All light-duty cars and trucks sold in the United States must meet the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards. To meet these standards, vehicles must undergo an extensive, long-established testing process, regardless of whether the vehicle operates on gasoline or electricity. Separately, EV battery packs must meet their own testing standards. Moreover, EVs are designed with additional safety features that shut down the electrical system when they detect a collision or short circuit. For more information, visit DOE’s Alternative Fuel Data Center.

The above info has been published on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, an Official Website of the United States Government.

1 U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA): Renewables became the second-most prevalent U.S. electricity source in 2020.

2 Assumptions: EV with 300-mile range; vehicle lifetime of 173,151 miles for both EV and gas car; 30.7 MPG gas car; and U.S. average grid emissions.

3 Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Energy Management Program, Bidirectional Charging and Electric Vehicles for Mobile Storage.

4 U.S. Driving Research and Innovation for Vehicle Efficiency and Energy Sustainability (USDRIVE), Summary Report on EVs at Scale and the U.S. Electric Power System, November 2019; and DOE, Electric Vehicles at Scale – Phase I Analysis: High EV Adoption Impacts on the Western U.S. Power Grid, July 2020.

5 Nature Energy, Charging infrastructure access and operation to reduce the grid impacts of deep electric vehicle adoption, September 22, 2022.

6 E & E News: Renewable Energy, Why Electric Vehicles Won’t Break the Grid, September 19, 2022.

7 US DOT FHWA (2018). 2017 National Household Travel Survey.

8 AAA Electric Vehicle Range Testing Report (pdf) (7.3 MB, February 2019)